Carved Wooden Spoon

By Gumuuinus de Eggafridacapella

Summary

The household item of the spoon is likely an Early Neolithic utensil, and spoons made from wood may have been created during this time. Due to the decaying properties of wood there are less extant artefacts, however the Oseberg find gives preserved examples. Wood-carving tools were most likely in use in the Viking Age, using forging methods in existence since 1st century. These tools of hardened steel would have refined the creation process for making wooden spoons. The techniques and tools used from roughly AD 820 are still in use today. I have used these techniques to craft a wooden spoon.

Introduction

Household goods and items are things which are used within households. They are tangible and movable items of property, and generally of a personal nature, found within the rooms of a house. For this topic, I chose to explore the creation of the humble spoon. The shape of the spoon may be scaled up or down as required, so it can be created as an eating utensil, with evidence suggesting those of Viking ways using smaller spoons for removing ear wax and measuring out cosmetics (MacGregor 1985).

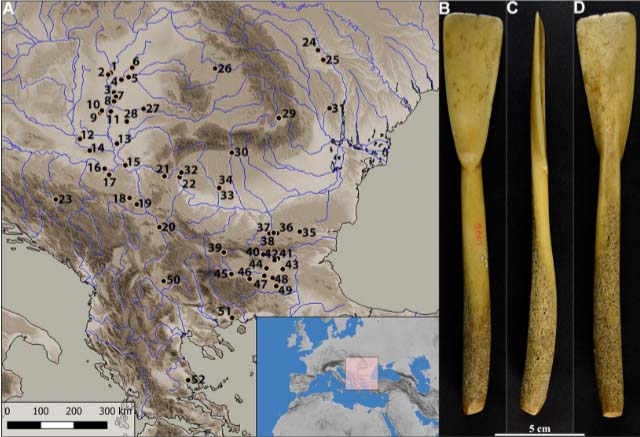

Spoons are the oldest eating utensil and date back to the Paleolithic age, originating likely in southern Europe (Stefanović et al. 2019). V-based cattle bone spoons dating from the Early Neolithic age were part of prehistoric weaning equipment of babies (Stefanović et al. 2019). These bone spoons show evidence of carving with sharpened stones (Stefanović et al. 2019).

The design of these spoons are shallow, indicating their use with a semi-liquid type of porridge (Stefanović et al. 2019). Animal milk would have been available in this area between 9000 to 8000 years ago, coinciding with the age of these spoons (Stefanović et al. 2019). Similarly, domestic cereals became available in this region between 9000-8500 years ago (Stefanović et al. 2019), providing alternative food choices and in turn accelerating the need to create spoons to bring these new food choices to the mouth.

In Ancient Egypt, spoons were made of materials such as ivory, flint, slate and different types of wood (Watson 2013). Greeks and Romans made their spoons from bronze and silver (Jones 2013). As the medieval times progressed, spoons were made from horn, wood, brass and pewter (Watson 2013).

Construction

Wood as a Medium

In the poem Húsdrápa, ca. 985, Úlfr Uggason described woodcarvings of mythological scenes adorning an Icelandic hall owned by the chieftain Óláfr pái (Schjeide 2015). Thus we know that the art form of skaldic poetry was presented on a wood-carved medium.

This description of poetry carved into wood indicates a sophisticated level of literacy, and we can infer that the actual finer carving of objects and items without a focus on writing literature would long pre-date this example. Archaeological finds of Viking Age (AD 800 – 1050’s) and early medieval woodcarvings exist, and Old Norse literature provides further clues to culture being infused into wooden objects (Schjeide 2015).

Archaeological finds throughout the landscape of present day Norway show us that during the Viking Age there was a rich tradition of production of both everyday objects and ornate luxury goods made by highly skilled craftsmen. Although in most cases these artifacts are limited to metal, stone, glass, antler and other materials that would preserve well, we can assume that wooden artifacts existed at the time.

The deduction of wood carving existing prior to 985 is further supported by the abundance of wood-carved objects found in the Oseberg ship grave mound (Schjeide 2015). This ship was built in AD 820 and buried in a grave mound 14 years later. The preserved wooden objects owe their survival to favourable conditions creating a low-oxygen environment, along with extensive reconstruction efforts providing a wealth of information for us. The Oseberg provides us examples of wooden spoon artefacts, among other wooden artefacts.

In the artefacts from the Oseberg we can see the use of oak, ash, pine, yew, maple and birch (Amberger & Braovac 2015). In Australia a lot of these timbers are not as easily acquired.

I used pine for my first attempt at wood carving, as this is an easily accessible softwood, making it easier to carve, and not expensive to acquire. Hardwood can be used for carving and while it is more difficult to shape, it has longevity and a deeper luster. Softwood can be prone to damage.

It is important to pick wood that does not have the pith or knots (formed where branches extrude from the wood) present as these provide hard points that are difficult to carve. These aspects can be removed with an axe prior to carving.

Green wood is a more ideal age of wood to carve, rather than one that has been drying for years. The amount of moisture assists with ease of carving. To maintain the level of moisture I kept my spoon blank in the freezer, thawing it out when I was ready to carve. In between short bouts I kept it in the fridge. Moisture can be reintroduced to the wood by spraying a mix of isopropyl and water to the wood.

Use of an Axe

Christensen (2008) notes that “both tool-marks and living tradition indicate that the axe was the most important tool used by all woodworkers”. Norway has yielded approximately 3000 axes in Viking-Age graves, with large numbers also found in Sweden and Denmark (Christensen 2008). The Oseberg ship provides evidence of two small axes being used as tools (rather than weapons), with them found with other kitchen equipment near a butchered ox (Christensen 2008). Thus the use of an axe is supported in woodworking techniques.

After drawing out the top plane of my design, I used the axe to rough out the shape of the spoon with small incisions. This helps to remove most of the excess bulk stock.

Stop Cut

Where the wood needed to ‘turn’ at the neck (where the handle meets the bowl) I cut in perpendicular ‘security stops’ or ‘stop cuts’ with the axe, creating a shelf so that the wood does not continue to split along these lines.

I then cut out the back face of the spoon, leaving it deeper around the narrow point of the neck. The grain flow changes direction here so leaving extra meat would mean I could correct issues if the wood started to crack.

Use of Carving Tools

Techniques can be gleaned from the relief carvings in the Oseberg find, where a knife could achieve most of the carving details (Schjeide 2015). More complicated relief carvings would have needed chisels and gouges to accomplish this, otherwise the variety of surface decorations could be made with a knife (Schjeide 2015). Mindfulness of the grain of the wood is demonstrated through the various hatching and chip patterns (Schjeide 2015).

The talented blacksmiths and metal workers of the time could have created specialized practical tools for a wood worker’s craft, with arguments supporting the existence of chisels and curved gouges in the Viking Age (Schjeide 2015). In circa 983, over the heath in Laxárdalr, it is likely the woodcarvings in Óláfr’s hall were created with aid of a V-groove parting tool (Schjeide 2015). A burial dating from the 9th or early 10th century contained a hollowing chisel (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018), supporting the argument for a variety of chisels.

I used the following knives:

- Mora 120 Sloyd Knife

- BeaverCraft SK4LS Hook Knife (left hand)

- Mora 164 Hook Knife

Figure 6: The Mora 120 has a short but wide blade with a full tang, giving strength and stability.

Figure 7: The BeaverCraft Hook Knife has a long handle to provide addition leverage, and a shallow blade to create smooth curves.

Figure 8: The Mora 164 Hook Knife is distinguishable by its pointed end and the blade has a smaller radius than the BeaverCraft Hook Knife, allowing for finer detail and deeper bowl creation.

Tools with Hardened Edges

93 intact socketed axes were found at Kohtla-Vanaküla, dating to the 1st and 4th centuries, with examples of socketed iron axes in use in Central and Western Europe during c. 800-1 BC (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018). Such axes could have been used as an adze by rotating the blade perpendicular the handle (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018). Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri (2018) thus speculate that such variations of the socketed axe and its range of uses could indicate a multi-purpose carpentry tool. I speculate further that this gives reason to think a collection of tools made fit for purpose could have been created for woodworkers.

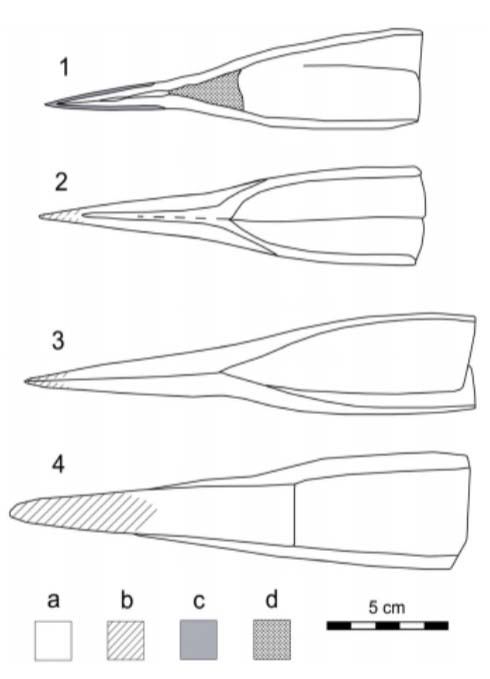

Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri (2018) found four types of forging patterns in the socketed axes studied (see Figure 10 below). While the core of the axe varied (with some having slag-rich iron cores and others having no filling to the blade core or socket), the cutting edge always consisted of a hardened edge (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri, 2018).

The first example shows a quenched and tempered martensite and this pattern of forging can date back to 3rd century CE (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018).

The second pattern of forging shows an extra layer of material forge welded to the blade, however no filling is added to the blade core or socket, and this method of forging was used in 5th-6th centuries Estonia (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018).

The third pattern of forging is simple where the axe is rolled and the blade is finished without adding extra components; this was used in 1st-2nd and 4th-5th centuries in Estonia, and later seen in the Oka river valley in the 5th and early 6th century (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018).

The fourth pattern dates from the 3rd to 5th century, with an iron socket welded on either side of an iron core, which has then been carburized to steel and tempered (Saage, Kiilmann & Tvauri 2018).

Regardless of time or complexity, this demonstrates that axes were purposefully created with a durable and hardened cutting edge. There is no reason to assume that this method of forging did not extend to smaller blades such as those used in woodworking.

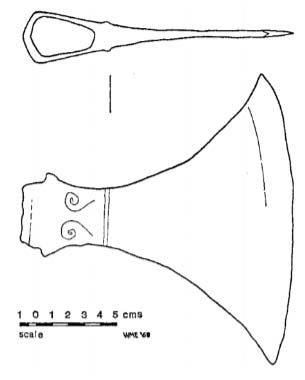

Softer metals used for the bulk of the blade allowed for decorating and engraving. Decorations such as inlaid strips of bronze are evident on the decorated axe-head of Viking type from Coventry, with the bronze embedded (but not flush) with the iron blade (Devenish & Elliott 1967).

Learning to Carve

The techniques used to create wooden spoons are likely to have been passed from carver to carver working together in close quarters (Stefanović et al. 2019). Studies on Bornholm Runestones and Slavonic pottery [both studies on items from the eleventh century and referred to by Stefanović et al. (2019).] suggest that technical execution would have been observed by the student, as similarities found could not be achieved by just providing models to the student. Viking mobility would have allowed for the exchange of information and techniques (Stefanović et al. 2019).

I had the benefit of being taught one-on-one by Little Spoon, following the traditions of seeking out a knowledgeable tutor. I reinforced my learnings via YouTube videos, in particular Anne of All Trades who provides woodworking techniques specifically tailored for female-built bodies.

The act of carving can take some time to get used to. The knives all handle differently, and there are several techniques that I needed to master.

Pull Cut

The pull cut draws the blade towards the body. The best way to do this is to brace elbows against the sides of the body and stabilize the spoon against the sternum. This limits the movement of the blade and will not allow it to injure you.

Push Cut

The push cut is performed by pushing the blade away from the body, usually pushing with the thumb of the hand holding the spoon. The travel of the blade is limited by the distance the thumb extends.

Running Cut

The hand holding the knife stays in place, with the hand holding the wood drawing the piece against the blade. This results in long, shallow and controlled strokes.

Finishing

Spoons are curved in all 3 dimensions, so revisiting those planes were necessary. Redrawing assisted in making sure the centerline was maintained.

I made sure the spoon bowl fit comfortably in my mouth, and the handle sat comfortably in the hand, as this spoon was designed for eating with. I sanded the spoon lightly with 400, 800 and 1200 grit sandpaper, giving it a smoother finish but not taking too much away from the roughened aesthetic of hand carving.

In between sanding, I wiped the spoon with a damp cloth. This removed the dust and assisted with ‘raising the grain’. The water causes the wood fibres to swell, and sanding after this is done is only to smooth the surface and not cut deeper – this would expose more grain which would rise again when wetted.

By raising the grain like this, the wood fibres should not swell as significantly in subsequent wettings, and the spoon shouldn’t feel as rough once it’s dried again. This should be done prior to applying water-based sealants otherwise the final finish may not be smooth.

At this stage, a stain could be added to the wood. This is best done after rising the grain, as the now-opened grain more readily accepts the stain (Miller 2020).

Sealing

I used a beeswax/food grade oil combination that functions to both polish and seal the wood. I use this on my wood products, whether they are furniture or mugs or jewelry, as it works as both a safe and period alternative to varnish.

Beeswax was used in the mummification process, and so its conservation properties are well-known (Abdikheibari et al. 2015). Blends such as beeswax-colophony (that is, beeswax blended with rosin) is used as a sealant mixture for preservation (Abdikheibari et al. 2015).

The recipe I use requires:

- 1 part beeswax

- 3 parts food grade oil

I use beeswax brought from a local apiary, which required straining and filtering. I store this by itself and double-boil portions of it on demand to combine with the oil for the sealant. It is best to use the double-boiler method to melt the beeswax rather than put it in the microwave as this can cause it to explode.

Once the beeswax is melted then add the oil – it will possibly solidify again so maintain the heat to melt the beeswax again. Keep stirring to combine the two ingredients. Once it is melted you can remove it from the heat and allow it to cool (or transfer to your storage container). This makes a food-safe product that can be stored as it is for a year.

To apply the beeswax sealant there is no need to re-melt, as the heat of your hands assists in melting the sealant as its rubbed in. Rub it in to all surfaces of the wood and allow it to soak into the wood for 15 minutes. If required, add more sealant. Rub off the excess with paper towel. This sealant also acts as a water-resisting agent.

The beeswax will melt off the spoon if exposed to heat, however holding the spoon and moving it over a source of heat such as a flame will allow the beeswax and oil mixture to penetrate deep into the wood. Keep adding sealant until there is residue left on the spoon, indicating it has soaked to saturation. Wipe off the excess. This method also serves to harden the wood.

An alternative to using this sealant, especially if the spoon will be regularly exposed to heat, is to use linseed oil (not boiled linseed oil as this has added chemicals in it). Some people dislike the subtle flavor linseed oil can give their wooden items, and it can cause a slight yellowing of the wood. Another food grade oil with a high boiling point can be substituted to treat the spoon without the beeswax. Regular application of the oil will assist with longevity.

Final Product

Figure 13: Front view of the carved wooden spoon.

Figure 14: Side view of the carved spoon.

Figure 15: Back view of the wooden spoon, showing the bowl, neck and handle.

Figure 16: Close view of the back of the bowl.

Figure 17: Close view of the side of the bowl, showing the way the handle meets the bowl, and the curve of the bowl.

Lessons Learned

Bowl

I started on the handle first and while this was not bad, I think that working the bowl first would ensure that the edge of the bowl is maintained, and that the handle can then flow from it more naturally. The back of the bowl near the neck was not terribly difficult to carve, however I was very aware not to make the bowl too thin.

Handle

The curve of the handle where it met the bowl was the most difficult part of this, given the way the grain wants to cut along the vascular lines. I nearly lost the bowl with a long split from over-eager carving and thoughtlessness. Careful stop cuts ensured that the bowl was saved and the split was carved out completely without destroying the functionality of the item.

Finishing

I did not burnish the spoon before sealing it. Burnishing is the act of rubbing the wood fibres together again. This is generally done with a smooth hardened surface, and anything from a rock to a piece of antler or the back of the carving knife can serve this purpose. By rubbing the surface of the wood it smooths and hardens the surface and sharp corners can be dulled.

Complexity

A less complex project may have been more ideal for a beginning item. A kitchen spoon would not need such sweeping curves in all three planes and can be much more ‘2 dimensional’ as shown by the Anne of All Trades free butter paddle template (Figure 18).

Conclusion

The humble spoon provides many learning opportunities to a beginning woodworker, teaching different cutting techniques as one navigates the grain of the wood. The techniques rely on tools that would have been refined since the 1st century. The accessibility of appropriate wood in the European countries would have allowed for whittling to occur during the spring and summer months. Armed with the right tools and knowledge, an experienced woodworker could create an eating spoon in a matter of hours.

The basic spoon pattern template easily scales up or down depending on the intended use, allowing smaller ones for ear cleaning and cosmetics measuring, to larger ones for stirring food-laden pots and serving meals. This is a simple pattern to replicate once the nuances have been visited and accommodated through practice, and thus ensures the regular household item of the spoon maintains its place in the home.

References

| Abdikheibari, Sara ; Parvizi, Reza ; Moayed, Mohammad ; Zebarjad, Seyed ; Sajjadi, Seyed. 2015. “Beeswax-Colophony Blend: A Novel Green Organic Coating for Protection of Steel Drinking Water Storage Tanks”. Metals (Basel). Vol 5 (3) pp. 1645-1664. DOI: 10.3390/met5031645 |

| Åhfeldt, Laila Kitzler. 2019. “Provenancing Rune Carvers on Bornholm through 3D-Scanning and Multivariate Statistics of the Carving Technique.” European Journal of Archaeology. 23(1), 82-104. DOI:10.1017/eaa.2019.37 |

| Amberger, Maria and Braovac, Susan. 2015. “Oseberg find”. UiO: Meseum of Cultural History, 18 December 2015. https://www.khm.uio.no/english/research/projects/saving-oseberg/oseberg-find/ |

| Devenish, D. and Elliott, W. 1967. “A decorated axe-head of Viking type from Coventry”. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology. Vol. 11, p. 251. |

| Hohler, Erla B. 1992. Wood-Carving. From Viking to Crusader: Scandinavia and Europe 800- 1200. eds. Else Roesdahl, David M Wilson. New York: Rizzoli. |

| Jones, Tegan. 2013. “The History of Spoons, Forks and Knives.” Today I found Out: Feed Your Brain (blog), 3 October 2013. http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2013/10/history-spoons-forks-knives/ |

| MacGregor, Arthur (1985) ‘Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn, The Technology of Skeletal Materials since the Roman Period.’ Barnes & Noble Books. |

| Miller, Gregg. 2020. “How to Raise the Grain and Stain Wood”. Hunker (blog). https://www.hunker.com/12498782/how-to-raise-the-grain-stain-wood |

| Saage, R., Kiilmann, K. & Tvauri, A. 2018, “Manufacture Technology Of Socketed Iron Axes”, Estonian Journal of Archaeology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 51-65. |

| Schjeide, Erik. ‘Crafting Words and Wood: Myth, Carving and “Húsdrápa”.’ Order No. 10086174 University of California, Berkeley, 2015 Ann ArborProQuest. 23 Dec. 2020. |

| Stefanović, Sofija, Bojan Petrović, Marko Porčić, Kristina Penezić, Jugoslav Pendić, Vesna Dimitrijević, Ivana Živaljević, et al. 2019. “Bone Spoons for Prehistoric Babies: Detection of Human Teeth Marks on the Neolithic Artefacts from the Site Grad-Starčevo (Serbia).” PLoS One 14 (12). DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0225713 |

| Watson, Gwen. 2013. “The History of utensils.” Food for Thought (blog), 21 January 2013. https://www.gourmetgiftbaskets.com/Blog/post/the-history-of-utensils |