Five 16-17th century Estonian Brooches and Pendants

By Muste Pehe Peep

In northern Livonia, during the 16th and 17th centuries, hoards of jewelry and coins were buried by peasant families, who had buried their meagre wealth for safekeeping. This was a period of upheaval, including the Livonian War (1558–1583) followed by the Polish-Swedish Wars (1600–1629) (Vijus and Vijus 2013:30), alongside the famines and epidemics of the early 17th century (Tvauri 2017:88). As entire families were killed in the turmoil, their silver remained hidden until their discovery (Tvauri 2017:88).

These brooches and pendants are not only significant due for their archaeological significance, or the reasons behind their burial, but because they also include inscriptions with names, unlike other engraved jewellery from this period with religious writing (Kirme 1986; Astel 2009; TLÜ Arheoloogia teaduskogu 2016).

Today, northern Livonia is the territory of the Republic of Estonia, and Estonia’s museums have been digitising their collections with images available online on the Eesti Muuseumide Veebivärav site (Estonian Museums web portal). It has become possible to view the jewellery mentioned by Arnek (2019:309) and Astel (2009), from a computer screen anywhere in the world.

Despite the various brooches and pendants being discussed from at least the 19th century, there does not appear to have been much discussion of the names recorded, with little attempt to provide an interpretation (Anonymous 1896; Astel 2009; Kirme 1986). I thought that it could be interesting to try to find parallels between the names recorded on jewelry, and other records from Estonia. While I was not successful in identifying all of the name elements (probably because I am not a fluent Estonian speaker), but I was able to find similar names in other sources from the 16th and early 17th centuries.

Ring Brooch

(National Museum of Estonia ERM A 555:128)

This silver brooch, reading “IAKVP x KVWA x POCK x 84” is dated to 1584 by Arnek (2019: 309) and Astel (2009: 32), and was found in a treasure hoard at Kureküla, Elva parish (formerly Rannu parish), eastern Estonia (Arnek 2019: 309).

Iakvp is clearly a form of the masculine name Jacob. Friedenthal (1931: 126, 128, 130) notes there was a goldsmithing apprentice in 1547 Tallinn called Jakup Blome, along with fellow apprentices named Jacup, Jacop and Jacob.

But Kvwa pock is less clear. Astel (2009: 32) interprets this name as a marked patronymic, “Kuuva poeg.” where “poeg” means “son.”

But while Roos (1976) has examples of bynames that are related to the moon, such as Kuwallo and Kuvalke (Modern Standard Estonian Kuuvalge, “moonlight”), it is not clear here, if Kvwa refers to the moon at all.

Paater Pendant

(National Museum of Estonia ERM A 509:687)

“Paater” pendants are a type of round, coin-like pendant that features religious imagery, such as Calvary or a St. Anthony’s cross (Astel 2009: 39). This pendant dates to between the second half of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Around the central scene, is engraved with PEPO TELCKE POICK (Astel 2009: 40). The original find location is unknown, as it was purchased in 1920 from an antique shop in Rakvere.

Pepo is a diminutive of the masculine name Peet or Peep, the Estonian form of the name Peter. Saar (2016: 40) states that the form Pepo was recorded in records from Tartu county between 1582 and 1588. Although it is clear that Telcke Poick is a patronymic ending in “poeg” or “son,” the first part of the name is ambiguous. Tiik (1977: 287) considers the names Tilcke (dated 1627) and Tillck (dated 1630/1), to be diminutives of the masculine name Philemon. However Saar (2008:52) interprets the name Tilk as a pre-Christian name used in the Võrumaa region. Saar (ibid.) mentions a 1561 record of Тилькъ Игаловъ сынъ (Tilk Igalov syn) from Pechory, Pskov Oblast, on the modern-day border with Russia. It is possible that Telke is a variant of these names.

Ring Broach

(National Museum of Estonia ERM A 509:684)

Unlike the jewellery mentioning Iakvp and Pepo, where the text is quite small, this brooch puts the name of a man front and centre: * IORGEN * MARTI * POIEKE. This inscription in modern standard Estonian would be Jörgen Mardipoeg, or “Jörgen Mart’s son.” Acquired from an antique shop in Rakvere in 1920, and now held by the Estonian National Museum, this brooch is tentatively dated to the 16th century by Arnek (2019: 309) and Kirme (1986: 43), and to the 16-17th centuries by Astel (2009: 36).

According to von Nottbeck and Neumann (1904:214), the name Iorgen was attested by a metal beaker that was held by the Brotherhood of the Blackheads, in Tallinn, with an inscription stating that it was gifted by Iorgen Goltsmedes to his guild in 1553. The name Martin was recorded in Livonia, as the form Mart. Stackelberg (1929: 117, 118) records in the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek, during the 16th century, a Mart Meysnick, as well as a Hannus Martipoick.

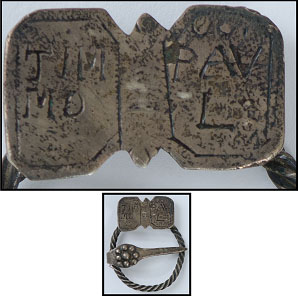

Penannular Brooch

(Estonian History Museum AM 8143 E 464)

This style of brooch, dated to the 16th to 17th centuries by Astel, was found at Tindi farm, Mulgi parish (2019:36). It has a butterfly-shaped plate where the name TIMMO PAVL was engraved.

This could be referring to a single person with an unmarked patronym, or is referring to two individuals. In 16th and 17th century Saaremaa, people frequently had unmarked patronymic bynames, so it looked like they had two given names. For example, Tiik (1977: 285) mentions Inge Andreß (ie. Engelbrecht Andreas), Hetto Maz (ie. Edward Matthias), and Olly Penno (ie. Olav Bernhard) in 1592. This trend in naming may also have been used on the mainland.

Although from the 14th century, and so earlier than when this brooch was made, Kaplinski (1975: 691) lists in records from Tallinn a Tymmo in 1371, and a Tymmo scomaker in 1374. Mägiste (1936: 48) considers the name Timmo to be a diminutive of Timoteus, or in English, Timothy.

I was able to find two instances of the name Paul on early 17th century Hiiumaa, with Paul Leypell and Paul Vßstall dated to 1645 (Kallasmaa 2010: 180, 471). However I could not find dated examples of Pavl or Paul in records relating to the mainland.

Ring Brooch

(National Museum of Estonia ERM A 509:601)

Unlike the jewellery mentioning Iakvp and Pepo, where the text is quite small, this brooch puts the name of a man front and centre: * IORGEN * MARTI * POIEKE. This inscription in modern standard Estonian would be Jörgen Mardipoeg, or “Jörgen Mart’s son.” Acquired from an antique shop in Rakvere in 1920, and now held by the Estonian National Museum, this brooch is tentatively dated to the 16th century by Arnek (2019: 309) and Kirme (1986: 43), and to the 16-17th centuries by Astel (2009: 36).

According to von Nottbeck and Neumann (1904:214), the name Iorgen was attested by a metal beaker that was held by the Brotherhood of the Blackheads, in Tallinn, with an inscription stating that it was gifted by Iorgen Goltsmedes to his guild in 1553. The name Martin was recorded in Livonia, as the form Mart. Stackelberg (1929: 117, 118) records in the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek, during the 16th century, a Mart Meysnick, as well as a Hannus Martipoick.

Conclusion

Intriguingly, all of these brooches have recorded the names of men. Kirme (1986:30) suggests that these brooches were given as gifts. It seemed assumed that these large silver brooches would have been worn by wealthy peasant women in the 16th century, based on artwork (de Bruyn 1581: f.77), 16th and 17th century written descriptions (Blumfeldt and Ränk 1935: 17-18; Põltsam 2002: 34), and later ethnographic data. Kindlam (1935) reminds us, however, that because jewellery was used to fasten certain garments in one part of Estonia, does not necessarily mean that it was used in only one way across the entire region. Similarly, some records only identify the area where they saw these outfits as Livonia, which could have been in the territories of Estonia or Latvia.

Despite uncertainty around how these brooches were used, and why they were inscribed, the recorded names do use patterns seen in other 16th century sources for Estonian names. Marked bynames using poeg, and unmarked patronymics, are also seen in data from 16th century north-western Estonia. Unmarked locative bynames, referring to a home village are also found in this region during this period. While these pieces of jewellery are often loosely-dated, and found across a wider region than the north-west, the names they have preserved do not appear to be out of place for 16th century northern Livonia.

References

- Anonymous, Katalog der Ausstellung zum X. archäologischen Kongress in Riga 1896 [Catalogue of the Exhibition of the 10th archaeological congress in Riga.] (Riga: W.F. Häcker, 1896)

- Anonymous (n.d.) Eesti Muuseumide Veebivärav [Estonian Museums Web Portal] https://www.muis.ee/ viewed 13 November 2020.

- Arnek, Pille, Eestikeelsed tekstid 16.–19. sajandi Põhja-Eesti hauatähistel. [Estonian-language texts on 16th-19th century North Estonian grave markers.] (Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikooli humanitaarteaduste dissertatsioonid 54, 2019.) http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:429651 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Astel, Eevi Eesti Rahvapärased Hõbeehted. [Estonian National Silver Jewellery.] (Tallinn: Eesti Pank, 2009.) http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:298341 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Blumfeldt, E. Räandnk, G, “Lisandeid Saaremaa etnograafiale XVII sajandi lõpult.” [Additions to the ethnography of Saaremaa from the end of the 17th century.] Eesti Rahva Muuseumi Aastaraamat, 1935, vol. 11, pp. 14–35. http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:367790 viewed 13 November 2020.

- de Bruyn, Abraham, Trachtenbuch der furnembsten Nationen und Volcker kleydungen beyde Manns und Weybs Personen in Europa, Asia, Africa und America Costume Book of the elegant nations and peoples clothes, both the men and women peoples in Europe, Asia, Africa and America. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55001874r/ viewed 13 November 2020.

- Eesti Keele Instituut (n.d.) The Dictionary of Estonian Place Names http://www.eki.ee/dict/knr/index.cgi viewed 13 November 2020.

- Friedenthal, Adolf, Die Goldschmiede Revals. [The Goldsmiths of Reval.] (Lübeck: Verlag des Hansischen Geschichtsvereins, 1931.)

- Kallasmaa, Marja, Saaremaa Kohanimed. [Saaremaa Placenames.] (Tallinn: Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 1996.) http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:280748 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Kallasmaa, Marja, Hiiumaa Kohanimed. [Hiiumaa Placenames.] (Tallinn: Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2010.) http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:280749 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Kaplinski, Küllike. “Eestlased ja venelased XIV sajandi Tallinna maksunimistuis.” [Estonians and Russians in the 14th century Tallinn tax lists.] Keel ja Kirjandus, 1975, vol. 11, pp. 682-692. http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:193474 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Kindlam, M. “Heart-shaped brooches.” Sitzungsberichte der gelehrten estnischen Gesellschaft zu Dorpat 1933, 1935, pp. 316-330. http://hdl.handle.net/10062/21051 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Kirme, Kaalu (1986). Eesti Sõled. [Estonian brooches.] (Tallinn: Kunst) https://www.etera.ee/s/Kn9syO6PoQ viewed 13 November 2020.

- Mägiste, Julius, Eestipäraseid eesnimesid. [Estonian First Names.] (Tartu: Nimede Eestistamise Liit, 1936.) http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:334837 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Põltsam, Inna, “Eesti ala linnaelanike rõivastus 14. sajandi teisest poolest 16. sajandi keskpaigani.” [The clothing worn by Estonian urban dwellers: from the second half of the 14th century to the mid-16th century.] Tuna. Ajalookultuuri ajakiri, 2002 vol. 2, pp. 22−43. https://www.ra.ee/ajakiri/eesti-ala-linnaelanike-roivastus-14-sajandi-teisest-poolest-16-sajandi-keskpaigani/ viewed 13 November 2020.

- Roos, E., “Inimene ja loodus muistses antroponüümikas” [Man and Nature in Ancient Anthroponyms.] Keel, mida me uurime. (Tallinn: Valgus, 1976), pp. 106–119. http://www.maavald.ee/maausk/maausust/eluring/2048-inimene-ja-loodus-muistses-antroponyymikas viewed 13 November 2020.

- Tiik, Leo, “Isikunimede mugandid Saaremaal XVI ja XVII sajandil.” [The adaption of personal names on Saaremaa in the 16th to 17th centuries.] Keel ja Kirjandus, 1977, vol. 5, pp. 284–288. http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:193488 viewed 13 November 2020.

- TLÜ Arheoloogia teaduskogu (2016). Eesti Muistsed Aarded. [Ancient Treasures of Estonia.] Online: https://arheoloogia.ee/virtuaaltuur/hobedasaal.html viewed 13 November 2020.

- Tvauri, Andres, “Three medieval and early modern hoards from Pugritsa village, historical Võrumaa.” Archaeological Fieldwork on Estonia 2016 (Tallinn: Muinsuskaitseamet 2017), pp. 81−92. https://arheoloogia.ee/ave2016/AVE2016_09_TVAURI_Pugritsa.pdf viewed 13 November 2020.

- Saar, Evar, “Rõuge ja Vastseliina talupoegade eesnimed XVI ja XVII sajandil,” [Peasants’ forenames in 16th and 17th century Rõuge and Vastseliina parishes] Õdagumeresuumlaisi Nimeq (Võro: Võro Instituudi Toimõndusõq, 2016.) pp. 11-55. http://www.digar.ee/id/nlib-digar:335303 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Saar, Evar, Võrumaa kohanimede analüüs enamlevinud nimeosade põhjal ja traditsioonilise kogukonna nimesüsteem. [An analysis of the toponymy of Võrumaa, from the most common name elements, and the naming system of the traditional community.] (Tartu: Tartu Ülikool, eesti ja üldkeeleteaduse instituut, 2008). https://www.etis.ee/Portal/Publications/Display/b590bece-187d-485c-a346-c49d7028e2da viewed 13 November 2020.

- Stackelberg, Fr Baron, “Das Älteste Wackenbuch der Wiek (1518–1544).” [The Oldest Wackenbuch of the Wiek.] Õpetatud Eesti Seltsi Aastaraamat 1927, 1929, pp. 78–254. http://hdl.handle.net/10062/20994 viewed 13 November 2020.

- Viljus, Aive and Viljus, Mart, “The Conservation of Early Post-Medieval Period Coins Found in Estonia,” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 2013, vol. 10 issue 2, pp. 30–44. http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021204 viewed 13 November 2020.